The first evidence that humankind knew about the special qualities of prime numbers is the Ishango bone that dates from 6500 bc, that was discovered in 1960 in the mountains of central equatorial Africa. Marked on it are three columns containing four groups of notches. In one of the columns we find 11, 13, 17 and 19 notches, a list of all the primes between 10 and 20.

The Chinese were the first culture attributed female characteristics to even numbers and male to odd numbers. The primes were macho numbers which resisted any attempt to break them down into a product of smaller numbers.

The ancient Greeks first discovered, in the 4th century BC that every number could be constructed by multiplying prime numbers together.

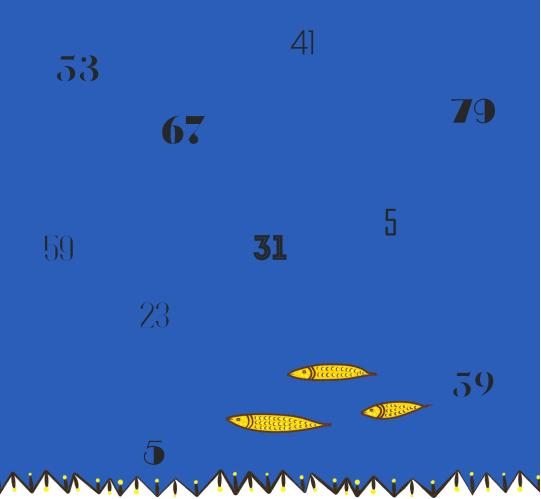

The librarian of the ancient Greek research institute in Alexandria was the first person we know of to have produced tables of primes. Eratosthenes in the 3rd century BC discovered a procedure for determining which numbers are prime in a list of the first 1,000 numbers. The procedure was later christened the sieve of Eratosthenes.

universal character.

universal character.

of the computer age.

of the computer age.

Gauss were

Gauss were  alive today,

alive today,

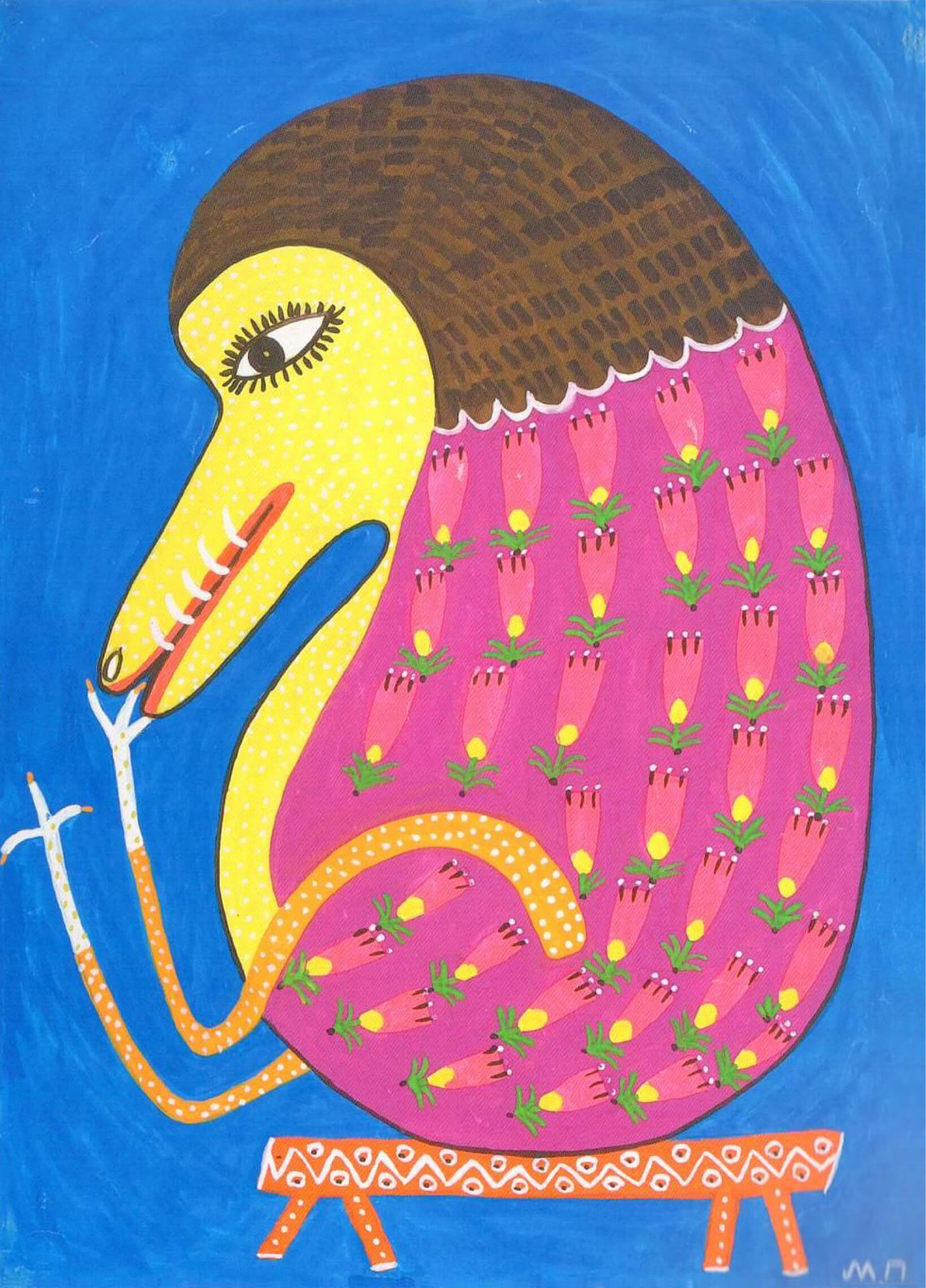

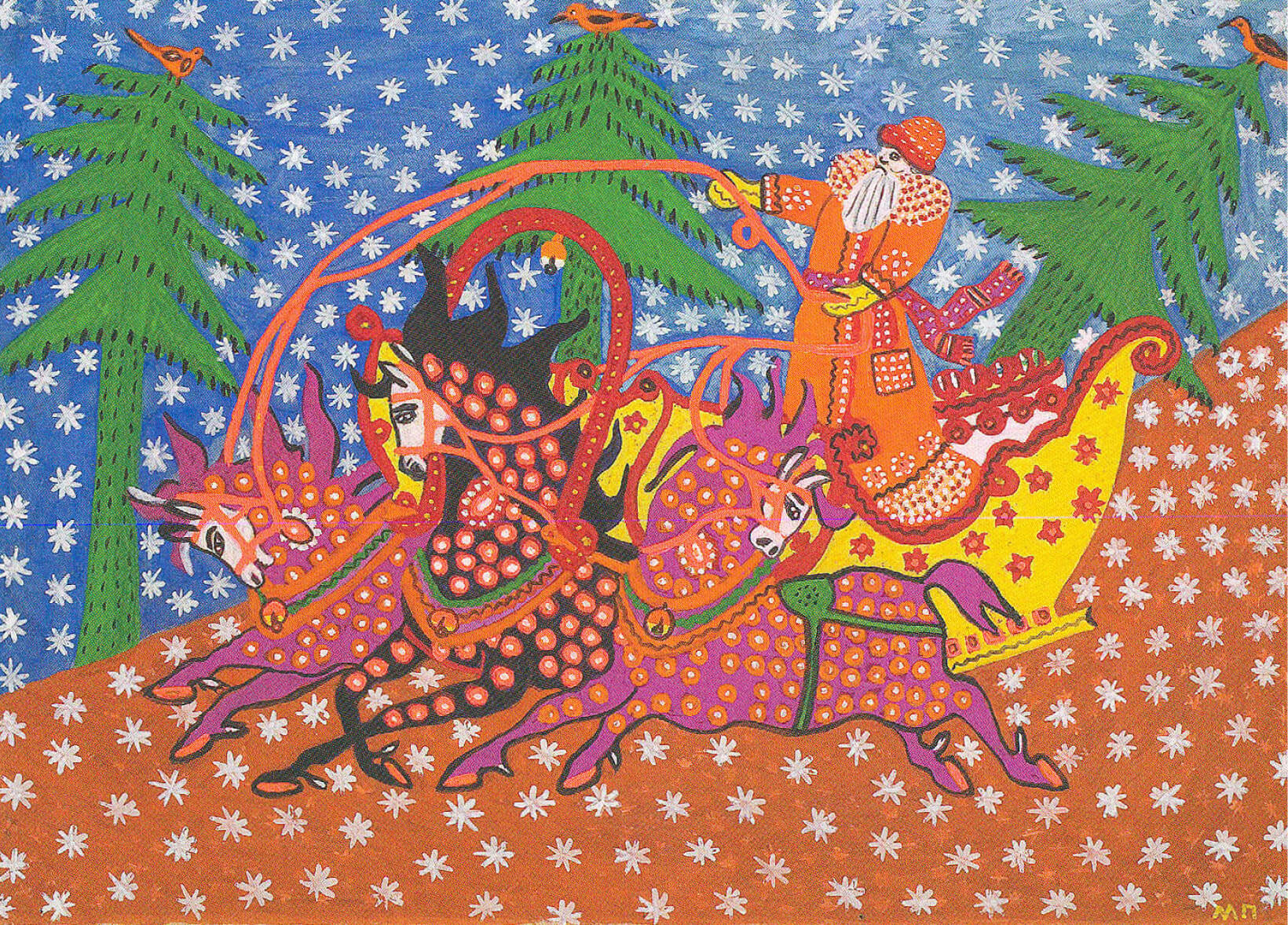

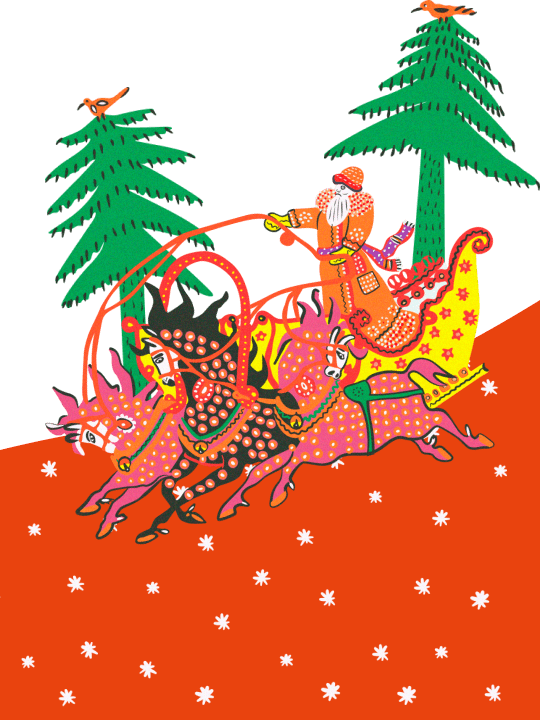

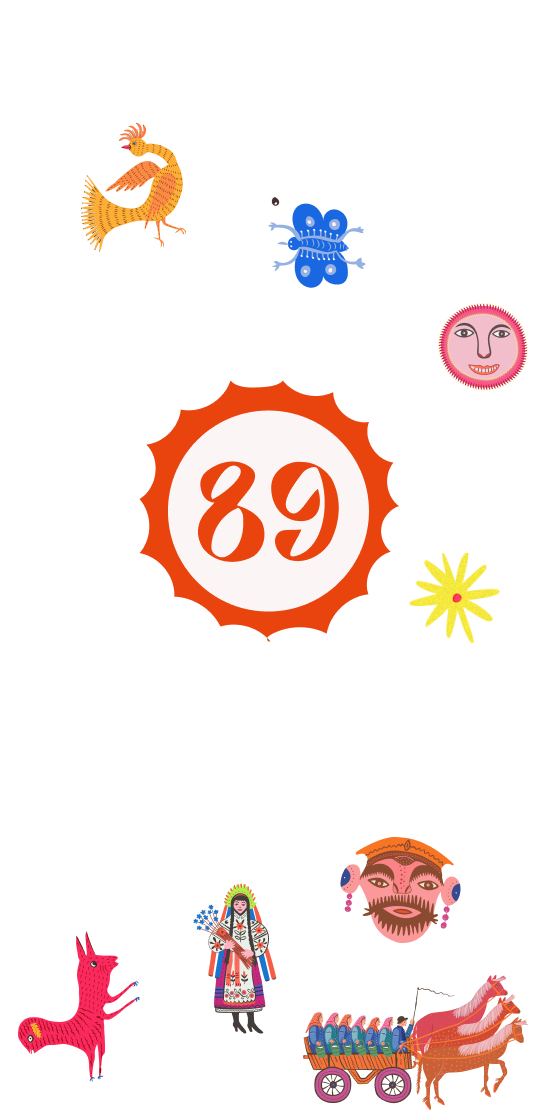

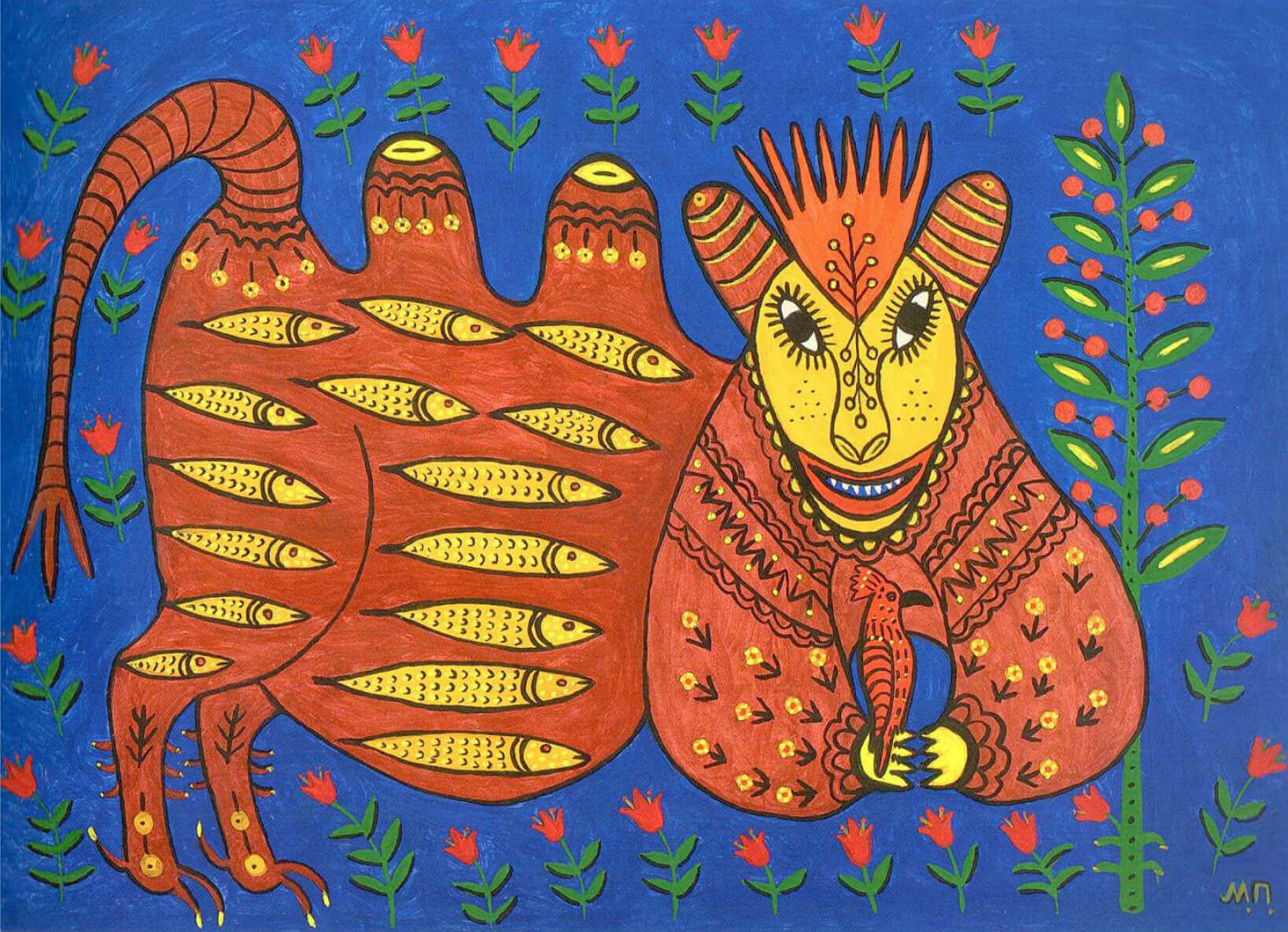

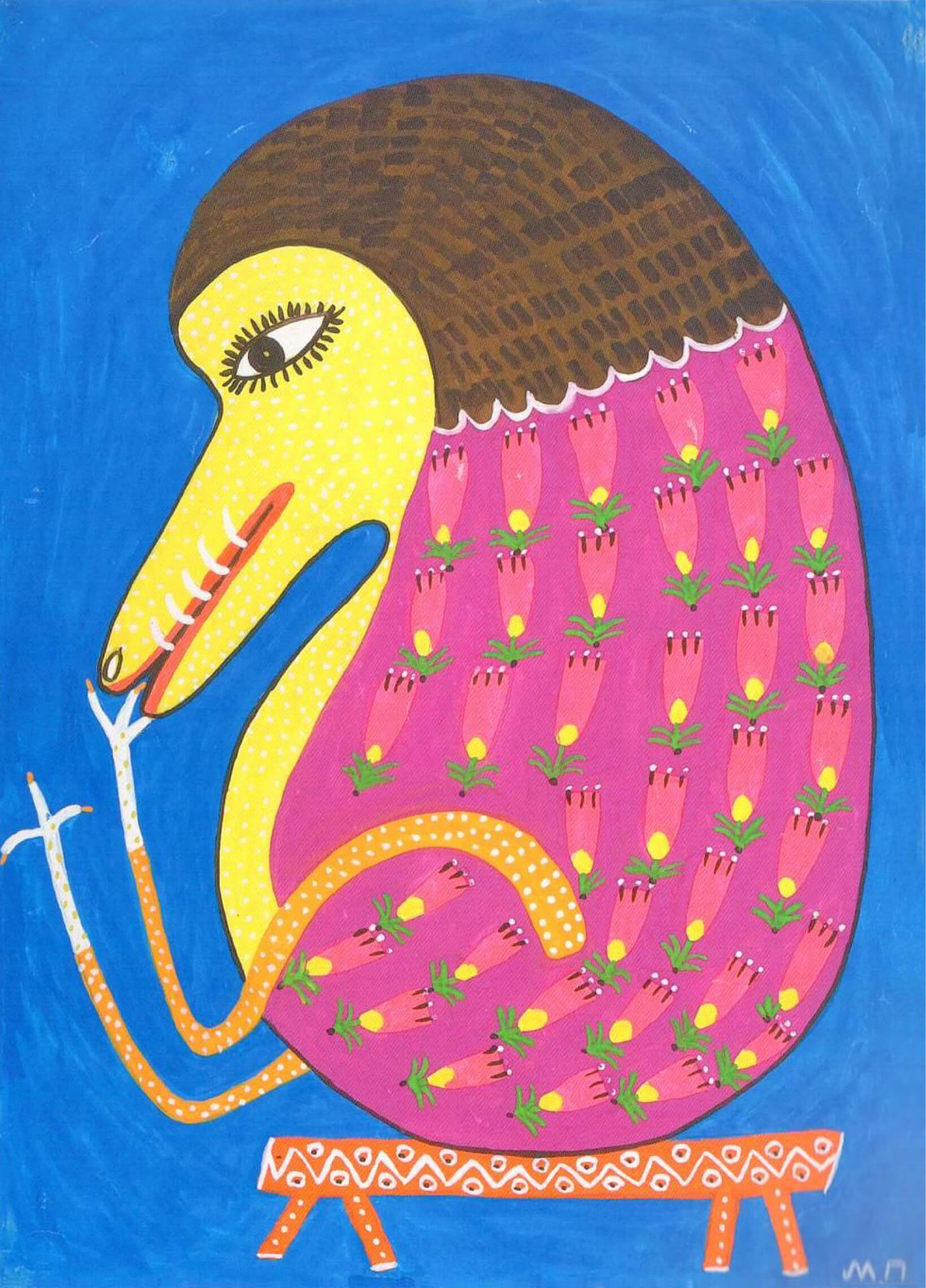

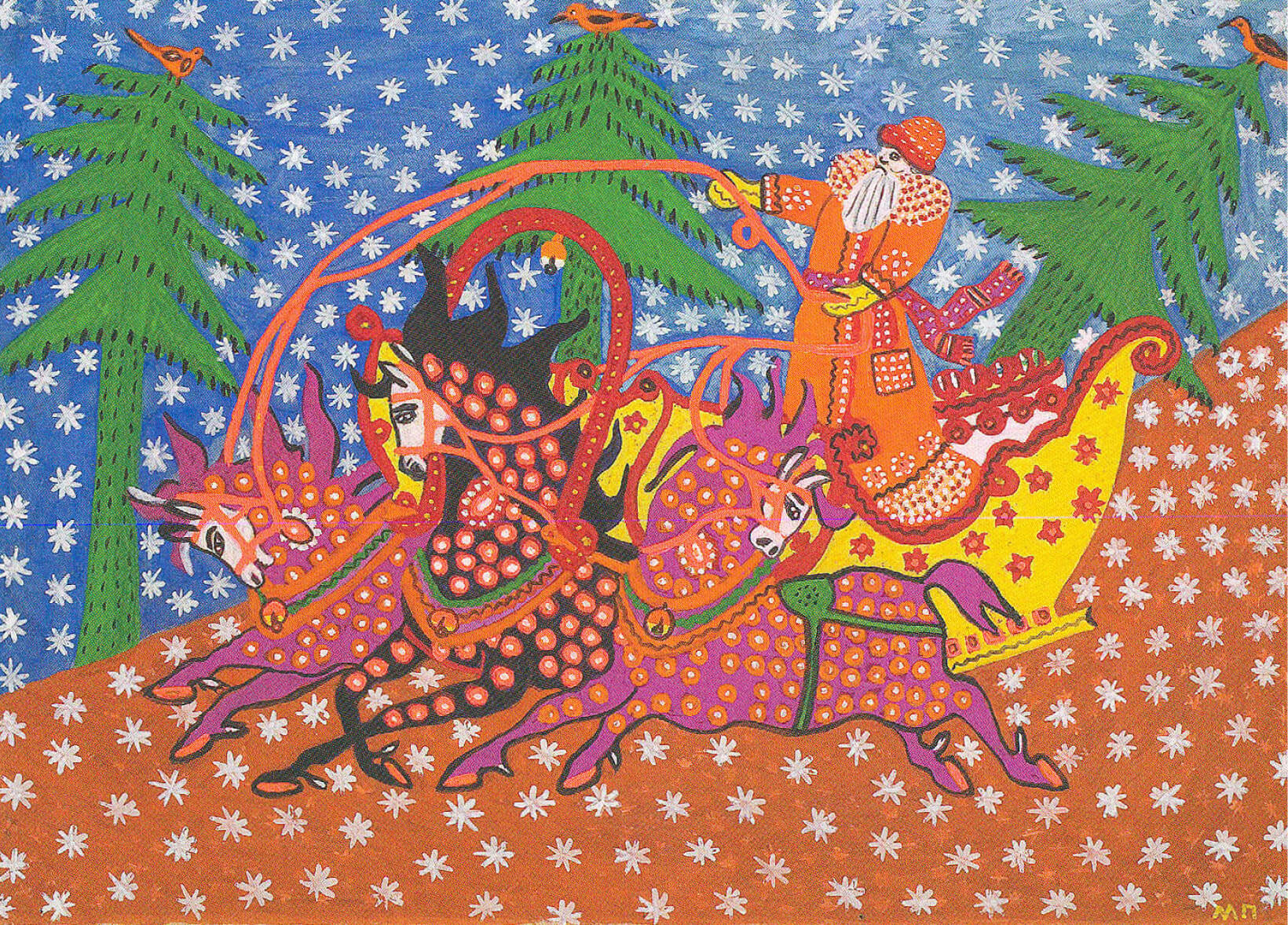

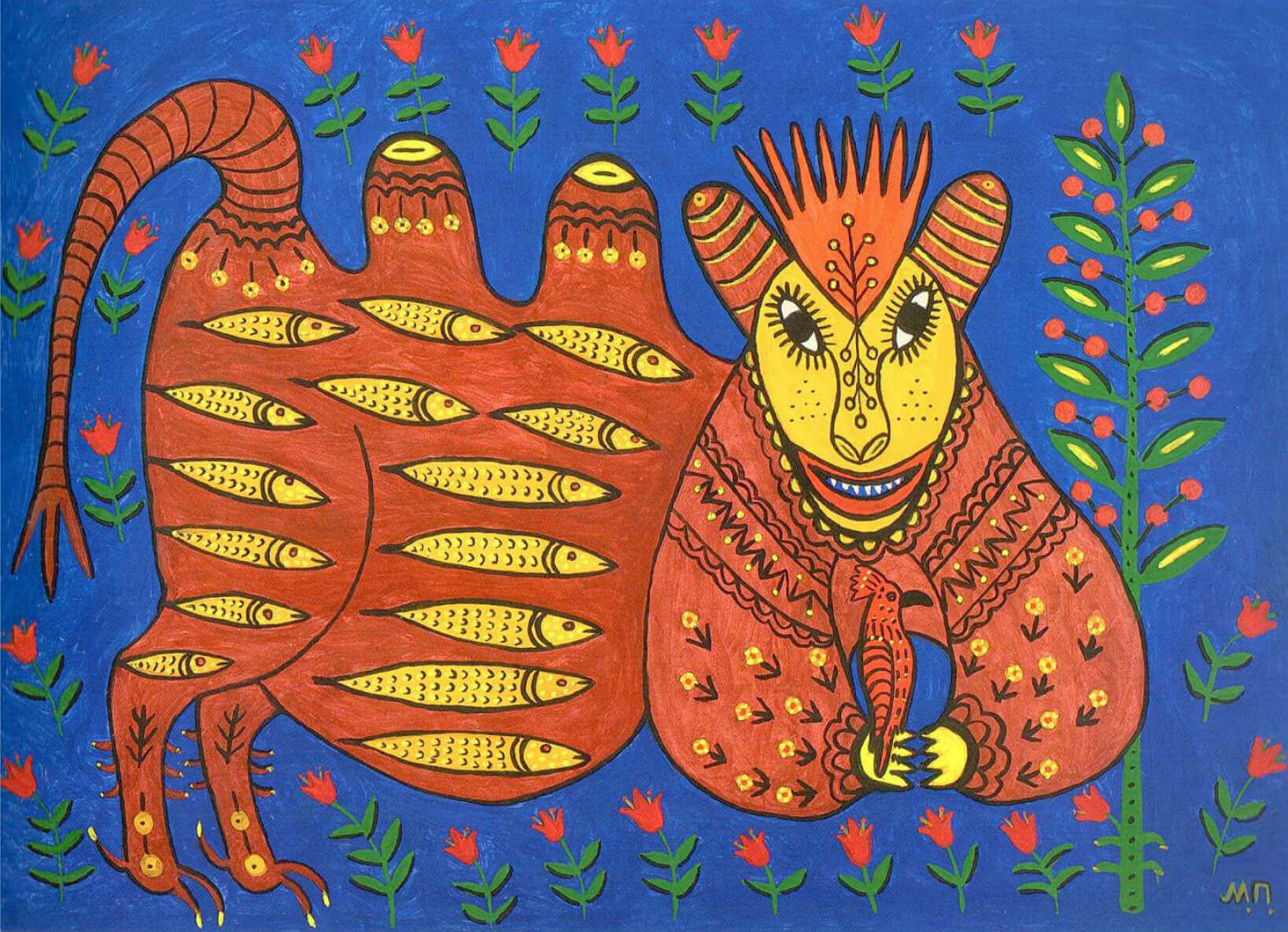

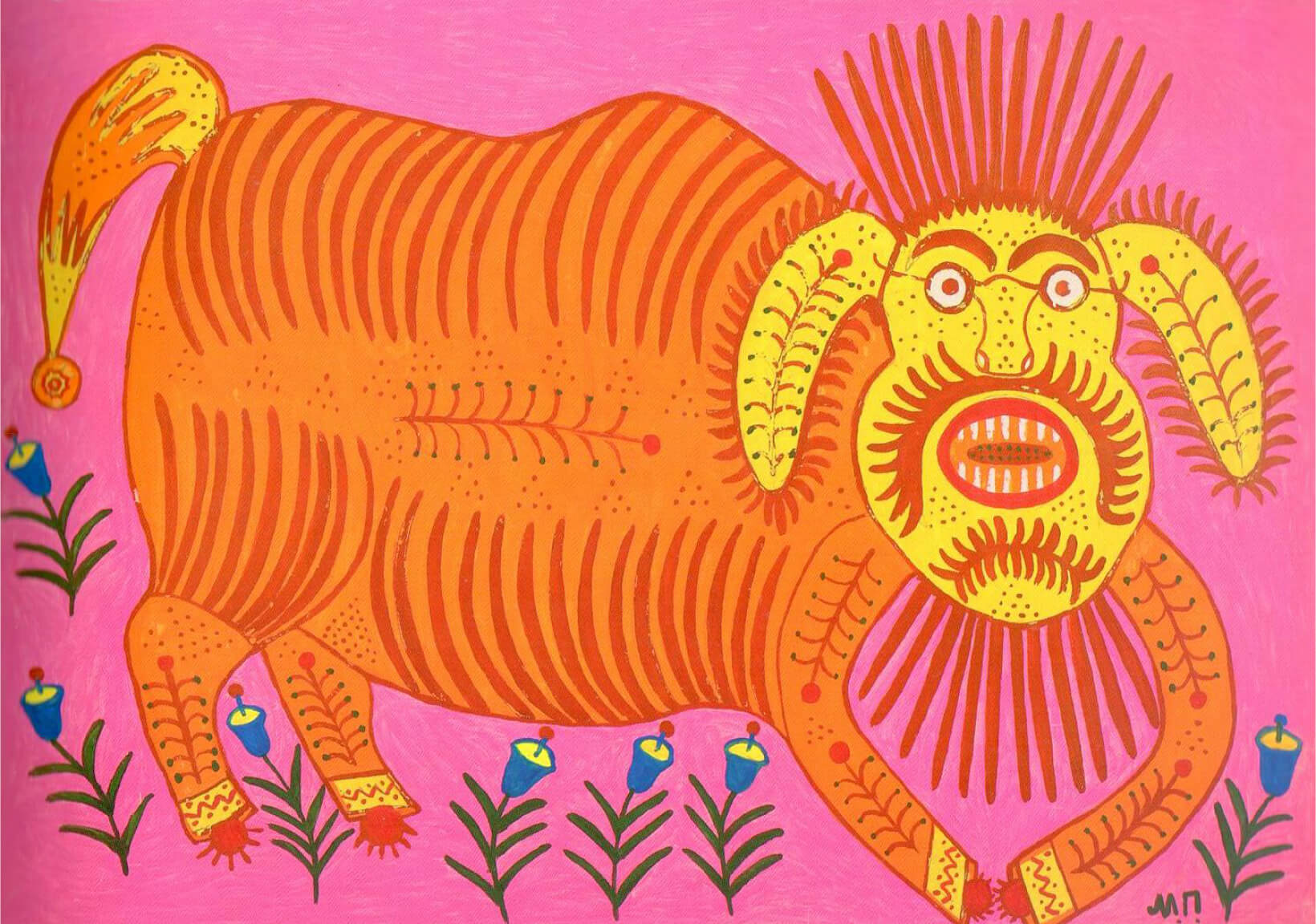

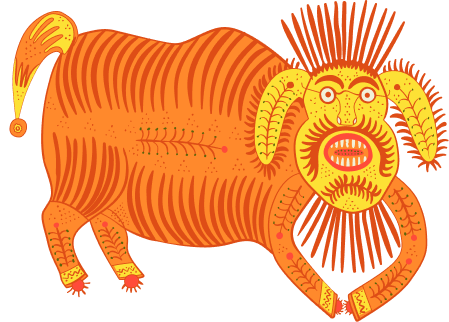

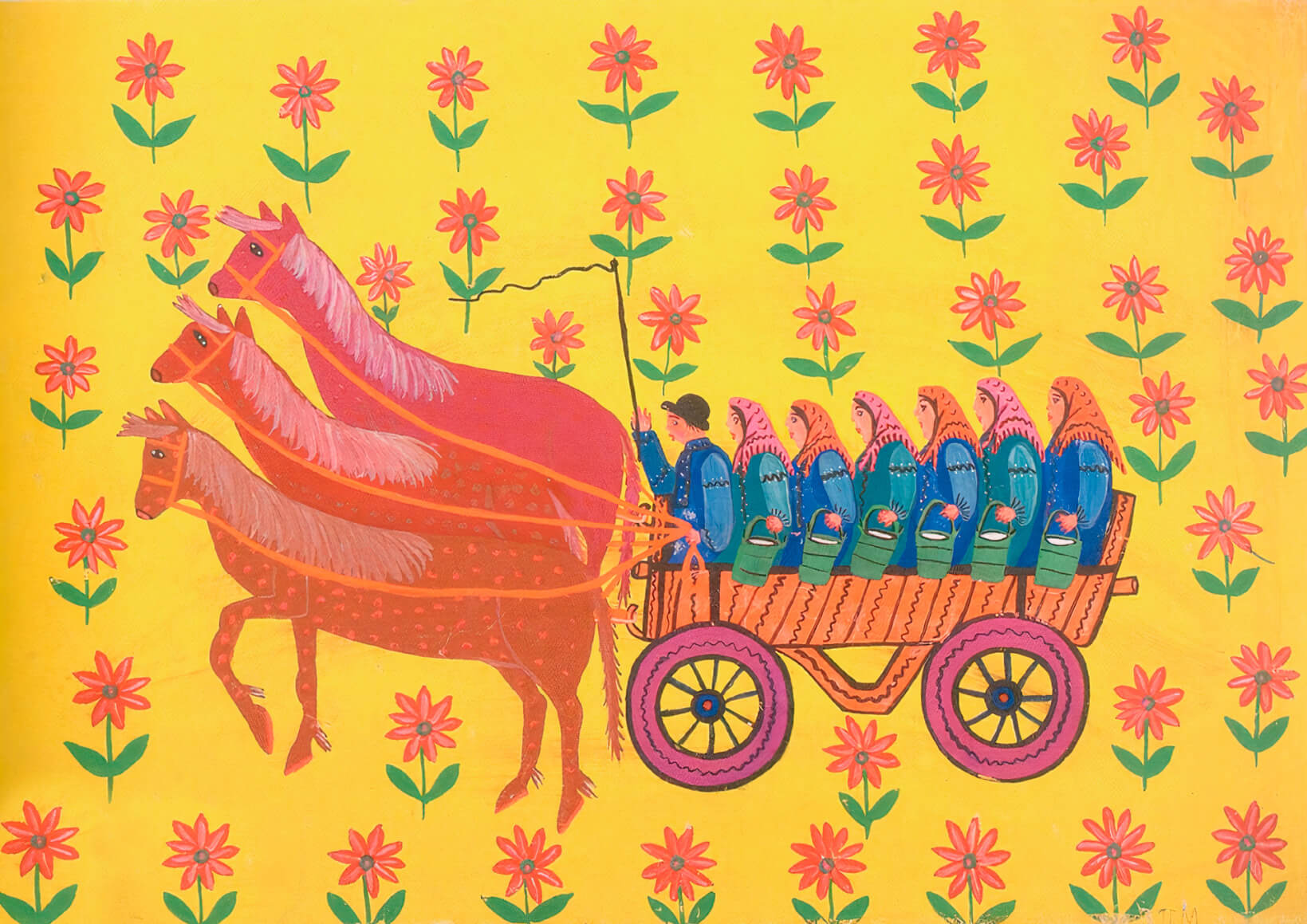

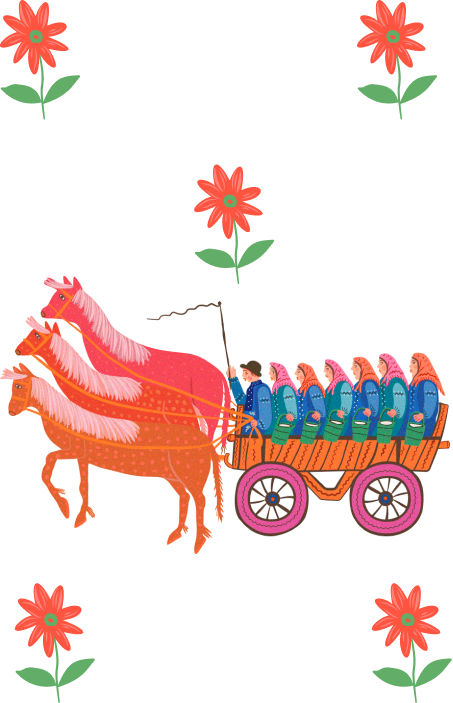

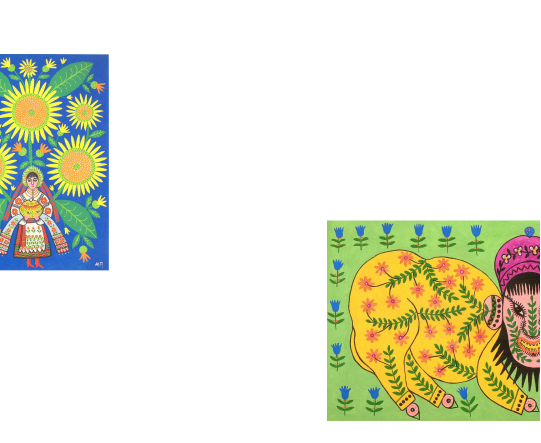

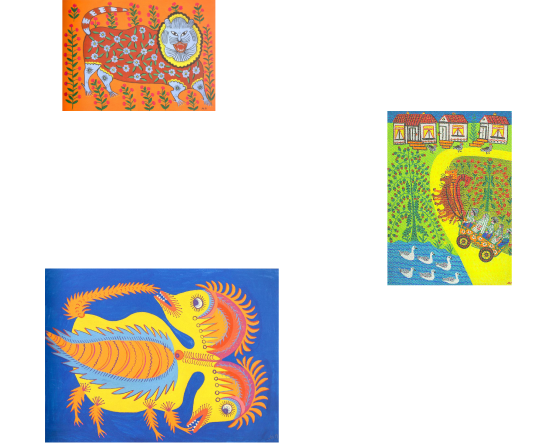

To support Ukranian

To support Ukranian

art and culture

art and culture

Gauss were

Gauss were alive today,

alive today,